By Ron Sharpe, his 4th grand-nephew.

George Whitelaw Kennedy 1823 - 1886

Early information on George Whitelaw Kennedy has been very difficult to obtain, and anything that has been gathered about his early life in Scotland has been sparse.

|

| Mrs Foote, via Ruth Chapman, Melbourne |

Early information on George Whitelaw Kennedy has been very difficult to obtain, and anything that has been gathered about his early life in Scotland has been sparse.

It is known however, that George was born at Dalricket Mill Farm, in New Cumnock, Ayrshire, Scotland, on the 31st of December 182. He was the 13th, and final child, of James Kennedy and Mary Young. New Cumnock parish records show that George Kennedy was christened on the 16th of May 1824.

The name of "Whitelaw" is not one previously recorded within the Kennedy family. It was initially thought that it may have been the maiden name of a family member going back two or three generations, but his parental grandparents were called McMillan and Currie and going back even further the names of Hamilton and McRae appear, but at no time does "Whitelaw" arise. However as Mary Young was born in Lanarkshire where Whitelaw was, and still is, a common name, it's possible that Mary may have had grandparents or great grandparents by the name of "Whitelaw". I should point out however that there is no evidence to support this and the theory is purely conjecture based on local facts, and the naming traditions of the time. George, as the youngest child, was the only one of Mary's thirteen children who was given a middle name. (George doesn't appear to have used the middle name until he got to Australia, on his 1856 marriage certificate. KM)

George certainly had an education, although as to how he received it, is again unsure. A parish school had been established in the town of New Cumnock by 1837, but that was four miles away from the farm, and anyway by this time, George would have been around thirteen and about to end whatever education he had been given. He would now be a strapping lad, ready and fit for the life of toil that was the norm for country families. The ability to read and write among country people, was not altogether common, and Illiteracy was not seen as a disadvantage, by many members of the farming community. Education was deemed as expensive and unnecessary to many families. Why would you need to be able to read anyway, when there was work to be done? You had no time to sit down and fritter good time away reading. However this was not the Kennedy family view of things at all, and there is proof of this, in a fact that turned up while researching George’s eldest brother Alexander. He had qualified as a minister in 1827 and went on to become one of the first missionaries to Trinidad in the West Indies, he was later to become a long serving minister in Canada. Around 1860 Alexander wrote a series of articles for the Canadian United Presbyterian Magazine. These would later be published in book form, and entitled "Memories of Scottish Scenes and Sabbaths of Eighty Years Ago". Although it concentrates mainly on religious life, it still gives us an insight into the Kennedy family’s day to day existence at Dalricket Mill in the early part of the nineteenth century.

George’s father was an elder of the Secession Church (The Box Kirk) in Old Cumnock’s Tanyard, and it's said that the minister of the time, Rev. David Wilson, and George's father, James Kennedy, were chief among the early influences that helped to form all of the Kennedy children's character. Religion at Dalricket Mill formed the mainstay of family life, and this is documented in the book, where it states that;

"James was known to have given religious instruction to all his children around the fireside".

This seems to point to the fact that James, himself, had at least, a rudimentary education. It has to be remembered that this would have been quite remarkable for a man who was born in 1776, the son of a weaver, who was probably poor and uneducated himself. James was going to make sure that his children were not going to be denied an education, at any cost. Another factor that may explain why all the Kennedy children were educated, is that Mary Young’s father was supposedly a teacher, and given that this is true, Mary may well have learned enough from him to give her own children a basic education. It's also known that travelling tutors toured the countryside in the early part of the nineteenth century giving lessons to country children, and James and Mary, regardless of the cost, may well have used the services of these people.

Dalleagles school was built about a mile from Dalricket Mill farm much later. It became a local school for country children, and the place where the next generation of Kennedy children would receive their basic education. An education so thorough, that many of these children would leave this small country school for university, and onwards towards a professional life.

A little more information came to light recently when a copy of George's obituary was discovered, that at least points to where he may have been between 1841 and 1851. On George's death the “ Ovens and Murray Advertiser ” of Thursday the 22nd of April 1886 states that

“ He was a native of New Cumnock, Ayrshire, Scotland, but had seen almost every town of importance in England, having for some time represented a Manchester firm”

This unknown information, changes many of our previously held misconceptions about George's early life before he sailed for Australia. I had believed he had worked on the land all his young life, but it appears that he was much more ambitious than that.

There's no doubt that George had a special spirit about him, and a sense of adventure seldom seen in many. These qualities, coupled to his need to escape the confines of his family and Dalricket Mill probably pointed him in the direction of England and the opportunities it seemed to promise. Did he follow some of his family and enter the drapery business? Scotsmen were commonplace among the drapery trade for some reason, and they were to be found all over the country working on their own account, or often employed by other Scots drapers who placed adverts for young men in the local papers in Scotland.

An example of the adverts placed in the local newspapers of the day

|

| Dundee, Perth, and Cupar Advertiser - Friday 05 January 1849 |

His elder brother John had left home in December of 1835 at the age of twenty, for Cornwall. It's not known what his intended occupation was in this far off English county, but it's a possibility that he could have entered the trade as he was later to establish a drapery business in Liverpool in the early 1850's, and he is believed to have founded a similar business in Canada even earlier. Whatever his trade was to be, both his father and mother gave him gifts on his departure. His mother gave him a dictionary and his father handed him a ready reckoner (the equivalent of a calculator today). These were hardly useful things you would give to a young man who was about to embark on a career as a ploughman. Whatever his intended occupation was going to be it was going to revolve around some form of business and required the skills of an educated young man. George was twelve, and would surely have watched his brothers departure with interest.

By the time of the June 1841 census for Scotland George was seventeen, and it's possible that he may well have left home, as he's not noted on the census. Dalricket Mill was at this time, supporting 13 adults and 6 children, spread over 5 families, however there's no sign of George.

There would have been great changes going on within the Kennedy family at the time, as George's father James, had died twelve days earlier. It seems strange, that the farm could support hired workers, but couldn't employ the youngest son of the recently deceased farmer. However, this may well have been George's decision as he appears to have been very independent. He may have already been distancing himself from the farm by working away from home. The census for 1841 was only held in Scotland, and the details were basically a list of the names, ages and occupations of the people. On looking through the census, there doesn't appear to be a George Kennedy living in Scotland on that night that fits his profile, and it may have been that he was resident in England or even Ireland. Of course he may have already been working as an apprentice with the “Manchester firm” at this time. The term in his obituary “had seen almost every town of importance in England, having for some time represented a Manchester firm” seems to tell us that selling and travelling would have been major requirements of the job but as to what form of business they were in remains a mystery.

But regardless of where he was living and working, George’s future within the family had already been marked out. Dalricket Mill Farm was now being run by his elder brother James. As mentioned above, the eldest son, and natural heir to his father was Alexander, but as he was a missionary in Trinidad by this time, he wasn't available to take over the running of the farm, and it's doubtful if he ever really wanted to. That task would therefore fall to the second son, James. This was probably a decision that had been decided, long before the birth of George, he was at the bottom of the pile after all, and he would have known that staying on the farm meant no more than a life of perpetual toil, his only way out was to do something about it himself. He was the youngest son and because of this, his future must lie elsewhere. The seeds of thought on emigration were probably being well and truly planted at this point.

When the second census came around, on the 31st of March 1851, George for some reason had returned to the farm, and was noted as a 27 year old unmarried farm labourer. This was a very different occupation from his previous job, it's not known why he came home. He would now be working a punishing day for, James, his elder, unmarried brother, and his future looked bleak. Although it's known that George had a real sense of adventure, the truth is, that it was probably just plain poverty, coupled to a huge will to achieve something with his life, that drove him from the hills of lowland Scotland.

Because of almost non-existent communications in the mid 1800s any news to reach Scotland was obtained by either word of mouth (often susceptible to untruths) letter, or the newspapers. News from the other side of the world was often three months old when it reached the UK, but by late August of 1851 the Times newspaper carried a report of gold finds in and around the Blue Mountain areas of Sydney . This news didn't start a stampede for ships passages, in fact the Times actually printed an article which was discouraging to any would be prospectors. “ It must be remembered that under the most favourable circumstances a very small proportion of the adventurers will reap fame or fortune … Almost certain disappointment … if not misery and death ... awaits the bulk of the 'adventurers' “

Nevertheless by the end of 1851 the news of the gold finds were widespread and ship's passages were being offered in large numbers. Did these newspaper reports spur George on? He would have read many adverts in the local press, where emerging parts of the great British Empire were requiring hard working young men, who were willing to leave home,and travel half way around the world in order to make their fortune. But these reports of the fabulous riches to be had in the emerging gold fields of Australia, where gold nuggets were to be plucked from the earth as easily as lifting potatoes, were beyond anything, any young man could have dreamed of. News broke in April of 1852 that three ships returning from Australia had berthed in London with part cargoes of eight tons of gold. Had George already made his mind up about Australia? Did this news confirm his decision? Perhaps Australia, would provide the opportunity for him to make his fortune, after all, many young men just like him were becoming rich in this far off land.

Before George finally left Dalricket Mill for what was to be the last time, there would have been some sort of family get together. Some of his closest friends would have visited all the farms and cottages surrounding Dalricket and tradition would have decreed that a collection was taken, “to give the young man a good start”. Family and friends would then have attended a soiree of some sort to wish him well and see him off.

George probably took leave of his family in Scotland and travelled to Liverpool sometime around May of 1852. His elder brother John had recently been widowed, and along with his young daughter Margaret, they had returned from Canada and now lived in Liverpool where John was in the process of establishing a drapery business. This now raises a question, Did George travel down to Liverpool to work with his brother in the drapery trade, or had he already made up his mind about emigrating while he was still living and working in Scotland? Many Kennedy family members did leave Scotland to work within the drapery trade, and this may have been an option for George. Many of the Kennedys had made huge fortunes in this trade, and with his brother already in the business, George's future would have been more or less assured. But if this had been the trade he had been involved in when employed by the “Manchester firm” he had probably had enough of sorting linen and serving woman with cotton and calico. This wasn't the adventure he had in mind, and it was never going to give him any sort of real satisfaction, and it seems totally ridiculous to imagine him as a draper. He was a real-life adventurer.

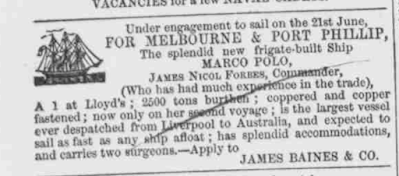

On the 18th of May the Liverpool Mercury carried an advert for “the splendid new frigate-built ship the Marco Polo, the largest vessel ever dispatched from Liverpool to Australia and expected to sail as fast as any ship afloat”

|

| Liverpool Mercury - Tuesday 18 May 1852 |

This advert is believed to have been the first mention of the Marco Polo's intended voyage to Australia. It was printed only nine days before George received his mariner’s ticket, (27th May 1852) which seems to say that George’s decision to join the Marco Polo and work his passage had not been pre-arranged before leaving Scotland, but had been a spontaneous one, made very soon after his arrival in Liverpool.

|

| Marco Polo by Thomas Robertson. State Library of Victoria |

George Whitelaw Kennedy, seaman, was issued with his Mariner’s Ticket (number 559,081) at Liverpool on Saturday the 27th of May 1852. He was one of thirty men who worked their passage. George was bound for the goldfields and he wasn’t coming back.

It’s unknown if the dates have any consequence but it does seem to be quite a coincidence. It must be assumed that the Black Ball Shipping Company thought that the voyage would be completed within this three month time frame, and they set their working contracts within those parameters. But did it really matter how long the agreement was for? After all, none of the crew could get off the ship until she arrived in Australia.

|

***************************

But would George really have had any idea just what almost three months at sea were going to be like?

There follows an account of the voyage by Ron Sharpe, his 4th great nephew, researched and written in 2014

I have recorded as many true facts about this voyage as possible from the diaries of passengers who were actually on board the Marco Polo with George. I have also researched similar voyages of the time and used some of the incidents and stories from passengers and records to fill out the story. To my knowledge George never wrote a journal and it should be remembered that these words are not his, they are the words of other emigrants, newspaper reports etc. and my own imagination. I have tried to weave these words into an interesting story of George's journey from Scotland to Australia. I would say that approximately 80% of these facts came from the voyage that George undertook and the rest are from other voyages, however, all are true.

Captain ‘Bully’ Forbes, the master of the Marco Polo, always believed that he had a lucky day, and his was a Sunday. On a previous voyage he had left Liverpool on a Sunday, sighted the Cape on a Sunday, crossed the equator on a Sunday, re-crossed the line on a Sunday and arrived back in Liverpool on a Sunday - so it was only natural that on the Marco Polo’s maiden voyage to Australia he should delay the start date from the Thursday 1st until Sunday 4th July 1852. The date had already been put back from the original sailing date of the 21st of June, so George must have looked out at dry land and Britain for a little longer than he thought.

Preparation For The Voyage

On arrival at Salthouse Dock I had my first glimpse of this great new ship that was to be both my home and my outbound ticket for the next four months. The Marco Polo was advertised in the local newspaper as a “Home at Sea“, and she truly was, for those with enough money to travel first class. At 185 feet from stem-to-stern, with three decks, and weighing in at 1625-tons, I was overwhelmed by the sheer size and outward beauty of this vessel. Two richly-coloured carvings of the great explorer Marco Polo himself, are attached to the stern of the ship. But I soon realised that my initial impression of the ship was tainted when I saw my accommodation. As working passage crew, we are the lowest class on board, neither experienced mariners, nor revenue producing passengers, and it seems we are destined to journey to Australia in the bow section, which is by far the worst part of the ship. I have very little room to move around and I’m told that I’m to be billeted here with all the other working emigrants for the duration of the voyage. Many of these young men are Highlanders and are very excited about the great adventure ahead. But although we all wish to get to the goldfields as cheaply and as quickly as possible, I believe that we must face the truth that we are going to find the whole journey very unpleasant indeed. My sea chest rests under my hammock and the ships carpenter has said he will secure it by some means in order to stop it from sliding all over the deck. He failed to inform me however of how I was supposed to achieve the same result.

The Captain who is from the great Scottish sea port of Aberdeen is reputed to be a tough man and after meeting him I believe that to be no idle boast. We (there are thirty of us) as passage workers would appear to be on the lowest rung of the ladder as far as respect goes, and his opening words to us were short, simple and brusque.

“An intending sailor should have above all things good health, and be stout hearted. Men, for the next four months this ship will be your entire world and you will find it to be a small one indeed. On board it does not matter from where you came from or who you are. You men are equal to each other. It would be wise to pull together and get along. A man who comes to work on board should be prepared to do anything at first that comes to his hand; and he should try to adapt himself to the ways of the new situation in which he has placed his lot. You will have many things to unlearn and also to learn. You must put aside your old ways and be willing to accept the new ones, if you can truly accomplish this you may indeed succeed here.”

These words made me realise that the lands around New Cumnock seemed very distant.

It’s Monday the 28th of June, and the last of the passengers have boarded, the ship has become very busy with great numbers of children running around and parents trying to make the most of the accommodation they have been allocated. By far the greatest number of passengers are Scots, over 600, and of these, a high proportion are Highlanders, with not a word of English. Many other passengers have been heard discussing how they will fare in Australia when they can’t speak a word of the language. But in my opinion these doubting Thomas’s have no concept of the Scot’s adaptability. I’ve never been to sea but I fully expect to survive this voyage and make my fortune, and I’m sure that the Highlander and his Gaelic language will also flourish. As emigrants we may have little or no money, but the Scots are a race of hard working, and God fearing people. With only these two attributes, we can, and will, prosper in this great new land.

Everything is loaded, stowed, and made ready for sailing, it has been hard work for the last few weeks but now as the sailing date approaches we are left with only a few small tasks to complete. My main duties will revolve around looking after the animals aboard, this involves mainly the feeding and cleaning of the beasts, and of course milking and collecting the eggs. I signed on as a seaman in order to work my way to Australia, but the first mate has decided that I would be perfectly suited to look after the livestock. Some horses and cattle are going out as “cargo”, while others are on board to provide fresh meat, milk and eggs throughout the long voyage. After spending much of my life in farming I don’t expect any problems, but I’m also required to work at whatever job is deemed necessary above decks. I fear this may cause me some slight problems to begin with.

We had an unfortunate incident in the night when one of the single women was said to have lost her reason. She leapt out of bed and with one of the lights in her hand, began to dance naked on the deck. She was restrained in some fashion, and the doctors conveyed her to the hospital. It is doubtful whether she will be allowed to proceed on the voyage

Tuesday the 29th was a truly auspicious day for everyone; The Marco Polo left Salthouse Dock. Although it was only a small journey into the centre of the river Mersey it had a profound effect on many passengers including me. As the tug took her in tow and she slowly floated away from the berth, her ships timbers creaked and groaned in complaint, reluctant it seemed, to slip her moorings and embark on the four month unending battle with the elements. It was at this point that I suddenly realised that the simple act of releasing the massive ropes that had bound us to the dock, had also, however gently, severed the final contact with my land, and my Mother. My dear mother, at what a cost to my heart this life changing experience is having. I am ready to go now, the more I stay, the worse it seems to get. We were supposed to sail on the 21st of June and I truly wish we had sailed as planned as my heart is full of thoughts of home and family and friends.

Wednesday the 30th of June was a special evening when a banquet was held on board, with a fine Instrumental band in attendance. I’m told that the guests were some of the most important people in the mercantile trade around Liverpool. I looked on from afar and pondered about the meal I would have that night, it would have little in common with the fine spread laid before the honoured guests, but on the bright side the band played some nice rousing music and that was a very enjoyable interval at least. Sleep came easy that night.

On Saturday the 3rd of July at about 11 o’clock a government health inspector came aboard and examined us all, including a baby who was born two days ago. He asked me if I was “quite well” to which I replied, yes. I thought this was a rather pointless question, and I was left to ponder what response he really expected me to give, this close to our departure date.

Captain Forbes showed himself to be every bit as heroic as his reputation suggested today, when he leapt overboard to rescue one of his sailors who had fallen into the river. He was none the worse for his unexpected ducking and the Captain seemed to shrug off the whole thing as an everyday chore. At around six in the evening a clergyman came aboard and conducted a farewell religious service on the poop deck. I was grateful of some spiritual sustenance and my thoughts that evening were of Dalricket Mill and my “ain folk”. We all sang the 64th Psalm “Hear my voice, O God, in my prayer: preserve my life from fear of the enemy”. He then offered up a prayer for the passenger and crew’s safety and welfare on the long voyage. This was followed by a sermon from Proverbs 16 “Wisdom is more to be desired than gold”. The speaker addressed us all in a very impressive manner reminding us that new scenes, new desires and new hopes were before us, but not to forget the one thing that was needful. I agreed not to forget my strict religious teachings and to be true to my God, but felt that I might be able to forego just a little more wisdom in return for just a little gold. He concluded his meeting when he touched on the parting of friends, and although this saddened me greatly it had an even greater effect on many others and had many of the passengers in tears. The minister ended with a blessing and a promise to us all that he would return early on the Sabbath morning. Very early on the morning of Sunday the 4th of July, the aforementioned clergyman returned to the Marco Polo for the last time. At the Captain’s insistence all available crew attended the short service and I joined in with everyone in the singing of the psalms and prayers. The minister offered his good wishes to all on board, and then quickly departed.

At 6.30 am the Marco Polo weighed anchor and moved under tow towards the Irish Sea. She was pulled by the little steam tug “Independence” I had little time to look back as the ship was pulled towards the open sea, and the sight of my homeland disappearing caused me great heartache. I’m sure I saw my brother John and my nine year old niece Margaret, standing on the quayside to see the ship depart. I waved with great vigour, but I quickly realized that John probably couldn’t pick me out from the huddled masses that were lining the ships rail, suddenly it struck me that John and dear little Margaret were going to be the last members of my family I would ever see.

Finally leaving Liverpool was such a strange feeling, I’d wished for it for such a long time, but when it finally arrived it saddened me greatly, and I found myself standing on the gently pitching deck, with tears welling in my eyes, unable to escape the heart rending crying and wailing of many of the emigrants. I tried to focus as much as possible on the two far off human shapes on the quayside, but of course eventually they blended into the overall scenery as I was borne swiftly away, and I realised that I was totally alone. Now I would just have to make the best of it.

Note; When George finally left Liverpool it had been a mere eleven months since news of the initial gold finds in Australia had appeared in the press.

The leaving of Liverpool

Our ship continued her slow progress under tow out of the River Mersey and searches were carried out to check for stowaways. The captain gave the order to “Search well below”, this order was quickly followed by, “and if you find any stowaways, put them overboard”. In a short time the cook reappeared with a terrified Irishman whom he had found concealed in the quarters of a married couple. "Secure him and keep a watch over the lubber, and deposit him on the first iceberg we find in 60° S.," growled Forbes, with mock fierceness. The stowaway, however, was returned to Liverpool in the tug. As the ship came about, the Captain ordered that two cannon shots be fired as a salute to those on shore. With the loud report from the cannon still ringing in our ears the ship caught the first breeze, and suddenly the canvas sails cracked and billowed outwards. The Marco Polo seemed to falter for a moment or two, and then almost without warning she seemed to sense the urgency of the moment. She reared up at the prow like a wild stallion, and surged forward as if running for her very life. Some of the passengers cheered, many cried and some, like me, once again just watched with a degree of sadness, as we finally took leave of this land of our birth.

As soon as the ship was under way and free of the tug, Captain Forbes had his passengers called together and informed them of his intentions on the voyage. We are to travel to the colony by way of something called the great circle route. He has charted this course in order to cut both the travel time and the inconvenience to the passengers.

|

| Wikipedia |

The great circle route will take us in a southerly direction down past the east coast of South America, and then steering south-east of Cape Town towards Antarctica. This path will take us as far south as possible without getting too close to ice and the dangers that that would present. Once we are that far south Captain Forbes intends to catch the “Roaring Forties”. These are exceptional prevailing winds that blow from the west to the east and which will fill our sails and guarantee fast passage. He will continue on this route until he reaches a point where he will head north into the Bass Straight between Australia and Van Diemen’s Land, and enter Port Phillips Head and onward to our final destination of Melbourne. He let it be known in no uncertain fashion that storms will not deter him and that it was his intention to be back in Liverpool by Christmas. Many of the passengers, laughed and openly scoffed, but nevertheless it has been the only topic of conversation on board since then. This has been a day of conflicting emotions and tonight after a great struggle; I finally managed to get into my hammock.

It has occurred to me that my life is now relying on something that is no more than a very small floating island. My life, for the foreseeable future, is going to be dependent on this collection of canvas, timber and tar, I can only hope and pray that the men who built her were conscientious craftsmen.

Monday 5th of July. This morning on being roused early to attend to my duties, I found the ship slipping southward through the Irish Sea encouraged by a steady breeze. Our situation afforded us fine views of Wales and in the far distance the coast of Ireland could be seen, but this soon gave way to the open sea, and a distinct change in the pitch and roll of the ship. I’d felt some discomfort earlier but now I am discovering what seasickness is. I’ve truly never experienced anything so debilitating and uncomfortable in my entire life. I’m told by Dr. North, who is one of the two Irish doctors on board, that it will pass once I “find my sea legs”, and that this is a common experience amongst what the old salts describe as “landlubbers”. I have decided to spend all my free time looking for these elusive legs, as the thought of four months without them seems unbearable to me.

Tuesday 6th of July. We’ve now left the sight of Britain behind us and are presently sailing off the western coast of France. The weather seems fine in general, although the sea appears to be rough in my eyes, but I’m told that I’ll soon be seeing much worse seas. I hope this was said in jest, as I really don’t know how I’ll cope with even rougher seas. Nearly everyone on board, with the exception of about 20, have been seasick since starting out, and it’s still causing me acute nausea and discomfort.

I observed my first whales today, and creatures that I’m told are porpoises. The whales keep a good distance from the ship but their position is soon given away, when they blow huge spouts of water to a great height. There are also a great many of these porpoises sporting about the ship, sometimes they leap two feet above the water so that we can see them quite distinctly. They are ugly brutes, and have a snout like a pig which gives them their name of sea pigs.

All of us have struggled to get into these hammocks where we are expected to sleep, and a great deal of practice is needed. We are in the dark here, as we are beneath the waterline at the bow of the ship, and our only light is from candles that we cannot light most of the time because of the risk of fire. The atmosphere is foul, along with the food, which for the most part is both meagre and of a very poor quality. The chief items of diet mainly consists of salt beef, preserved potatoes, porridge and ships biscuits which are hard and have little flavour. I have brought some of my own food with me, but, like our drinking water, it won’t last very long . We have already ran out of fresh water twice down here as the diet is so salty and we have all decided to collect rain water whenever we can. The food for the passengers is much better of course and they often dine on such things as suet pudding, boiled pork, ham or meat pies, pea soup, jam dough, and rice pudding. But I suppose that as I’m saving the steerage fare of 25 pounds by working my passage, I can’t expect too much.

Thursday 8th of July. The ship is now off the “Bay of Biscay”, I’ve been on watch all night, along with other crew members and some of the passengers who take their turn in rotation. The seas appear rougher again but the weather in general is holding up, with little rain, but stronger winds which are propelling us along at a pace. I’ve been told a child died last night, this has been the first death on board. I’m concerned that there will be many such deaths before we get to Australia. There are a great number of children on board. We communicated with a French vessel at around six pm last night. She’s bound for England and will report our position.

Friday 9th of July. We have light northerly breezes this morning. We’ve been ordered by the Captain to get cleaned up and be on deck at 07:00 am to attend the funeral ceremony for the child who died yesterday. A weight was placed in the box along with the little corpse. However when the makeshift coffin was confined to the deep, it steadfastly refused to sink and was still floating on the surface when it disappeared from view on the horizon as the ship was propelled south. This caused great distress to the parents and a great many passengers.

Saturday10th of July. It’s now six days since we departed Liverpool and we’re presently off the most southerly tip of Portugal at Cape St Vincent, around 1200 miles from Liverpool. I finally feel as though I’m beginning to overcome the dreaded seasickness. The seas are relatively calm and although I have felt decidedly queasy I’ve managed to keep my food down.

Sunday the 11th of July, it’s now one week since we left Liverpool and it seems that my sea legs have finally come out of hiding. Although nothing seems to have changed as far as the pitch and roll of the ship is concerned, little by little I seem to have become more agreeable to its behaviour. Today I’m told by Dr. North that we are now having a few attacks of dysentery and one woman in particular was so sick as to cause him great concern. We are currently sailing on light breezes and are on a course of S.W. by S. I have observed no particular change in the climate until now, but this day is very warm and the loveliest sky I have ever had the pleasure to look upon. We have had prayers read and a sermon preached twice today. I thought that as the most of the emigrants were Scots that we ought to have had a Presbyterian minister or at the very least one from the Church of Scotland, however it seems an English lay preacher is to attend to our spiritual needs. The Highlanders are quite distressed at the lack of a preacher who they can understand, and it seems they are to be given permission to conduct their own Gaelic services. In the evening we communicated with a schooner out of Oporto in Portugal; she was bound for Liverpool and will report our position. We also signalled to a Portuguese Man of War.

Tuesday 13thof July. In the evening we had a great deal of some floating substance which I cannot describe, shining on the surface like witch-fire. Some say it is a kind of fish of which I am doubtful. The calmness of the sea and the pleasant climate in the evening brought many of the emigrants above decks to enjoy the air. Some of the passengers got together after a while and started playing a deck game called pass or catch the slipper. This lead to some of the younger ones singing and very soon thereafter singing and dancing was started among the many different cultures.

One of the Highlanders had a set of bagpipes while another played the fiddle. As I stood and watched this great exhibition of merriment it soon occurred to me that this community of almost a thousand souls were beginning to bond into a group. After all, we only had each other. For the most part, with the exclusion of any family we were travelling with, we’d left everything else behind us, probably for ever. It seems as though we are already forging a second culture, it seems to me that we are already becoming Australians.

Wednesday 14th of July. After the great entertainment of last evening, we have been brought back down with the news of the death of another child on board. Owing to low breezes we have been making very slow progress and there appears to be no wind on the horizon.

Thursday 15th of July. The ship is totally becalmed off the island of Madeira, and the sails hang limp and useless from the spars. We have a good view of the island, and after days of seeing only sea and sky something such as this creates a great interest among everyone. There are many small whitewashed houses perched on the lower slopes of what seem to be rather high mountains. This morning at six o’clock we had a funeral service for the child who died yesterday. Because of our stationary situation and the distress caused to the passengers only a few days ago, it was decided to put a few extra chain links in the coffin. This time the tiny coffin was confined to the deep with great speed, much to everyone’s relief. After the funeral ceremony The Captain and two of the officers went out in a small boat and we think this was to try and discover how the current was set. A large turtle came very close to the ship, and the captain tried to catch it from the small boat but with no success. The wily old turtle will live to tempt another crew another day. It appears that all the singing and dancing we had on Tuesday has promoted the forming of a vocal club. The group comprises of thirteen people and they will practice every day on the quarter deck, as long as the weather permits this. The weather has been very agreeable today but without a breeze the sun is very hot. However the evening sky is like something I’ve never seen in my life before, this is truly Gods own creation. A child was born today. What an amazing world we all live in, God takes one child’s life and gives life to another. He truly moves in mysterious ways.

Friday 16th of July. We’re still becalmed, and although there are some light breezes, they just don’t have enough strength and consistency to fill the canvas and carry us forward. Today the decks are full of people who are glad to enjoy the warm rays of the sun and just relax. While others have grabbed this respite in the constant rolling deck to wash their clothes, and bring up their bedding from below to give it some air. At times you could easily be mistaken for thinking that the entire human cargo comprises of only children, there are over 300 on board, and they are always getting into scrapes of some kind or another. One of them fell down the main hatch today, a distance of about 17 feet, but had a miraculous escape and suffered very little.

Saturday 17th of July. Our prayers have been answered and we’ve finally been given some breezes although it was into the afternoon before it arrived. Many of the 1st class passengers are complaining of the discomfort they are having to suffer due to the great heat inside their cabins. We have rigged up an awning of sailcloth on the deck to give some shade from the fierce rays of the sun, and small sails have been set by the hatches to catch any breeze and try to blow it down below to the passengers quarters decks. This is all that can be done for their situation, but once the ship is underway, cool breezes will soon repair this. Where I am billeted with my colleagues, the heat is much worse and very little air circulates. As a result of this we would rather work above decks as much as possible, and on stifling nights I’ve been glad to sleep here as well. Some of the crew went out in a small boat this morning after they spotted a log of wood but they found it to be of no use, and left it.

Earlier today there was a great number of fish congregated around the ship. This prompted many of the passengers to try their hand at fishing, but they had serious competition in the form of a large dolphin who, it has to be said was much more successful. The dolphin has a beautiful appearance in the water, its colour so transparent. One of the two doctors on board has told us that the ship now has an outbreak of measles and that it’s spreading very fast, however he said that it was a mild form and should amount to little more than annoying itching.

Sunday 18th of July. Fourteen days out of Liverpool and at 06.00am this morning we crossed the tropic of cancer 20 degrees west of Greenwich. Captain Forbes has, by his exceptional seamanship, managed to catch the trade winds and we are now scudding before a fine and powerful breeze. We have as companions a great number of flying fish which are swimming and flying alongside us. They are about the size and shape of a Loch Fyne herring and can travel at such a great speed that when they leave the water they can glide from 10 to 100 yards at a time We sighted Palma today which is one of the Canary Islands. Another child died today, she was only fourteen months of age. I do find these young deaths very hard to bear.

Monday 19thof July. We are still making a great pace and although we have no sight of it I’m told by the mate that we are now off the coast of West Africa. The weather is very hot today but as we’re moving along quite swiftly, we all benefit from the cool breezes. One of the sailors was put in irons this morning on the charge of being too familiar with a single female passenger from Edinburgh. I have no idea of what his fate will be, but it’s well known among the crew how the Captain disapproves of such behaviour. All the crew and single men are berthed forward, with married couples and families amidships, and single women aft.

Tuesday 20th of July. Another child passed away today, one of the ship’s surgeons said it was caused by water in the head. The voyage was never going to be easy, but these deaths of the young are so hard to bear for everyone on board. It's sixteen days since we left Liverpool now. Sixteen days ago we were all as good as strangers to each other, but these deaths feel so close to us all, and are having a profound effect.

Burial at Sea

Wednesday 21st of July. At 01:00 pm today we are within two miles of St. Antonia which is one of the Cape de Verd islands of the coast of West Africa. It’s a small isle about 15 miles in length, although the general appearance is of a burnt nature, the scenery is really magnificent and we can easily see the mountains. I borrowed a telescope and could view the land quite clearly. I observed some green patches which were obviously being cultivated. I was told later that these were probably vineyards. I have started to notice a distinct change in my complexion and my face and arms appear to be taking on a much browner appearance. We passed an American whaling ship which was cruising along the coastline.

Thursday 22nd of July. We have sighted five ships today, however all of them were distant and steering a northerly course. Another child died this morning and it was decided to have the funeral as soon as possible due to the great heat we are experiencing. The breath had barely left the little ones body when we committed it to the deep. It is heart wrenchingly difficult to have to watch the parents stare out to sea afterwards, looking as if they had accidentally thrown a precious belonging over the side. Even though I have now experienced a few of these funerals it still troubles me greatly. The decks are much quieter now as a great deal of the children are sickly. This mild outbreak of measles seems not to be as mild as first thought.

Friday 23rd of July. We have passed through the trades now and have picked up the variable winds north of the Equator. The weather is once again very warm with light winds which propel us forward, but at a very slow pace. One of the female passengers while taking some exercise on the deck, accidentally fell down a staircase a distance of around eleven feet. Mrs Pender, had her young son William in her arms at the time, both mother and child miraculously suffered little from the fall and are recovering.

Saturday 24th of July. On watch duty early this morning, there are stiffer breezes and the seas are getting rougher, however it calmed down later in the day but we were subject to heavy rain showers at night and I took the opportunity to try to catch some to help replenish our drinking water, but a large wave broke over the bows and filled my pot with sea water, rendering it useless. Yet another child died.

Sunday 25th of July. Little wind this morning and we are once again almost becalmed, we have achieved little more than ten miles in a nights sailing. After our religious service was over this morning, the Captain, with a hook, line and a piece of pork for bait caught a three foot shark, which after a great struggle we managed to land on deck. It’s said to be one of the most dangerous creatures in the ocean and that reputation is no less true when it’s out of the water. Once landed it immediately became a wet, writhing demon with razor sharp teeth that it seemed determined to sink into anyone’s leg who got close enough. The boatswain got behind it and managed to dispatch it with a heavy blow to the back of the head. The Captain was happy to gift this devil of the sea to his men and the boatswain immediately began to dissect it. The cook prepared a meal of it, and although a bit salty, it was very fine eating indeed.

We caught up with three other vessels in the afternoon who were heading in the same direction as us. One of these was the barque Shanghae, out of London and bound for Melbourne. Captain Forbes decided as we were almost becalmed, that a little socialising would not be out of place. A boat was lowered and swiftly dispatched to the Shanghae. On its return it brought the Shanghae’s captain and five of his officers aboard the Marco Polo. They remained on board for around five hours and on their departure they looked as though they had enjoyed themselves greatly. Captain Forbes accompanied by three of his officers joined them on their return to their ship and stayed for about four hours before returning. This evening we have a light wind and heavy showers of rain. I’ll try and collect more rainwater this evening.

We are sailing very fast today and the strong breeze gives us some respite from the heat. The cook killed a sheep this evening and his butcher's knife broke. As it was of little use to him he threw it overboard, but as he was throwing it, it caught one of the passengers in the eye and cut it very much. But the bleeding was quickly stemmed thanks to the swift efforts of Dr North.

I was witness to another death this evening, this time a little girl of two and a half years old. She had been very ill for the past few days and Dr North had mentioned his concern for her. As I was passing the family cabin, I saw the mother crying. I went to the cabin door, and there was the poor little thing gasping for breath, and making a queer noise in her throat. The mother could not bear it and had to be lead onto the deck. The father said to me she is dying. I said I hope not. Yes, he said. Its eyes were set then, and I went in and for the first time in my life saw the breath depart from one.’

The next morning I ‘rose at half past five and went to the hospital to help the sail maker sew the little thing up. We placed two large pieces of chain at the feet to make it sink. I then went on deck and it was a most splendid morning, the sun just rising. We laid the corpse on a board and covered it with the Union Jack, two of the sailors carried it to the side of the deck, and rested its feet upon the side. The father and mother and eldest daughter followed and stood behind crying. The Captain read the burial service and when he came to the part – we commit this body to the deep, they raised the head and the body slipped off into the sea with a sudden splash and sank immediately. The cry of the mother at the moment the body fell was dreadful.

The father standing behind the mother and daughter with his arms around them both, all crying. It was indeed a pitiful sight. Although these child deaths have become frequent and we are almost used to dealing with the effects of them on a daily basis, it doesn’t stop the whole situation being very difficult to bear. I can remember this small child in the early days of the voyage as a smiling happy little girl moving around the ship on shaky legs, to have seen her breath her last was upsetting to say the least. Many of the passengers and sailors were very upset and I will never forget the emotion and sympathy I felt for that broken family that beautiful morning.

But God does indeed move in mysterious ways, and no more than an hour after the sad burial of the little child, news of the birth of a baby boy reached us all, and great was the joy for the child and his family. It seems that there’s a custom on immigrant ships to burden the newborn with the ship’s name. However the McLaren family believe that Marco McLaren doesn’t quite have the ring to it that would belie the child's proud heritage of old Scotia. This wise decision to adhere to the old Scottish naming tradition has resulted in him being named William, which I’m sure will be a great relief to the child in the future.

The weather has become much warmer as we race towards the equator or the “Line” as it’s referred to by the ships company. The heat is unbearable at times and almost everyone has dispensed of many of their heavy weight clothes as the heat makes them a hindrance when working or just moving around. You could find no comparison to the conditions we presently find ourselves suffering from, anywhere in Scotland. It is almost as if we are sailing towards the gates of Hell itself. In the early part of the voyage we caught sight of many other vessels quite frequently, and we signalled one or two; but now we seem to be on this great wide ocean all alone and see nothing excepting sea and sky. We lost view of the “North Star,” a few nights ago and now “The Plough” it seems, has also deserted us, in fact all the stars of the Northern Hemisphere are no longer to be seen. I suppose this is another landmark occasion on my continuing voyage south towards Australia.

It’s now mid-August and we are five weeks out from Liverpool. This morning, we crossed the equator. I’ve been told by the first mate that there’s to be a traditional ceremony this evening, one that until now I was unaware of. His description of the ceremony seems decidedly pagan and unchristian to me, and my feelings are that I want no part of it. The Captain has forbidden the crew from any interference with the passengers, but any member of the crew who has never experienced King Neptune and his family are to be considered fair game, and as I’m working my passage, I, along with many of my shipmates, will have little choice as regards being a part of this so-called ceremony.

In the cool of the evening around nine o'clock, as I stood on the deck taking the air, I was accosted by a number of fellows and carried towards the fo’csle where I saw some of my fellow crewmen. A loud shout soon informed me of the approach of his Majesty, and rockets immediately flew up, along with blue lights which were burned, and threw a most unearthly appearance around the ship. Presently old Father Neptune made his appearance on the fo’csle, and a more scary looking fellow, I never saw. The crown on his head was dazzling in its brightness and the trident he carried, although it appeared to have been made from an old broom shaft, was a truly formidable affair. The captain quickly seized his trumpet, and blew a unearthly screeching note. At this signal Neptune’s henchmen flew about, causing great consternation among the passengers who were taking a great interest in this entertainment. King Neptune was dressed in an old cloak which was in turn, attached to what looked like the teezed out fleece of a recently deceased sheep. He marched, colossus like and with a stately step to his throne. Alongside him was his rather large wife who sported a very noble set of whiskers from one ear to the other, and she in turn carried their baby son who bore a strong resemblance to a piece of wood.

When I gazed on Neptune’s face beneath his coarse wig of even more sheep fleece topped with his gold crown, I felt awed. And when I looked on his grizzly beard and beheld his noble face and prominent nose, on the point of which danced a clear little sea drop. I felt I was in the presence of royalty, or was that the first mate I recognised? Neptune’s royal party were accompanied by a group of six sturdy fellows who were dressed as policemen and numbered from 1 to 6, as well as a fearsome chap who took on the role of the barber. The barber was a great personality, and what a shudder ran through the audience, when he opened up his five foot razor and felt its saw-toothed edge. Neptune chose certain crew members, of which I was one, and the policemen were despatched to bring us all in front of him. While we stood in front of Neptune, we were blindfolded and had our hands tied behind our backs. In this condition we were asked sundry questions and had our characters investigated. Our answers to these enquiries was to determine what edge of the razor we were to be subjected to.

Of course, we all had to be washed first, and then our faces were doused with soap for our appointment with the barber. The barber went on to make a great play of shaving us although he never allowed the “razor” to actually make contact with our beards. When the ordeal with the barber was over we were then plunged back into the large tub; and to keep us company several lookers-on were also shoved in and there we were all tumbled about gloriously, like so many porpoises in a tea-kettle. By and by the tub was upset, and the water flowed about everywhere, and over several of the onlookers. Neptune’s wife then danced a jig while his barber menacingly flourished his razor among the crowd. Very soon after this the royal party departed the fo’csle and the daily monotony of the voyage quickly returned, everybody it seems was very amused, although thoroughly ducked.

Once we had crossed the “line”, Captain Forbes took full advantage of every breath of wind and set all possible sails to catch and exploit them. These actions propelled the ship south at a great pace and on reaching the small island of Tristan da Cunha we turned and caught the “Roaring Forties”. These powerful winds were to our great advantage, but as we were now so close to the icy wastelands of Antarctica, they were intensely cold. The cold winds around the lands of New Cumnock in mid-winter could not at all be compared to them. The first mate has told me that this is as far south as the Captain wants to go as there is a chance of encountering ice. I wonder how something as trivial as ice can concern a man of Captain Forbes's ability. But as it seems to get even colder the further south we go, I find I’m more and more content with his decision. We have rushed out of the heat of summer into the depths of winter with a rapidity which has taken most of us by surprise. We have had bitterly cold days and snow showers, and the sun setting at 4.30 in the month of August. Sleeping without rocking is unknown here.

As we continued to sail east towards our destination we experienced frequently wild seas and stormy conditions. The winds steadily increased and the waves rose higher as we plunged headlong into the furious brine. The ship rolled and creaked like a crazed and wounded animal, and it was only possible to stand still by holding on to a solid object. However it became a challenge to avoid every conceivable item that wasn’t fastened down, as these were being thrown across the ship, only to return a few seconds later along with items from the opposite side. As most of these items were made of tin, the noise, along with the constant shrieking of passengers, who were convinced they were about to drown, was horrendous. The weather was so bad at times and the pace so relentless that the Captain's actions scared many of the passengers who feared for their very life. They became so concerned about their safety that they sent a deputation to him beseeching him to shorten sail, but Captain Forbes was in charge of this ship. After he'd given the deputation his curt refusal he added that it was a case of “Hell or Melbourne”. No other choice it seems, is going to be made available to anyone.

On many occasions my four hour duty watch was almost unbearable, the ship rode the waves and wind, like a bucking horse, water rushed over the decks making the ship seem so small in God's great, great ocean. I had lashed myself to the fo’csle with a stout rope, and all the while I was being thrown from one side of the ship to the other like a child’s rag doll, struggling and straining to see a safe passage through the freezing, stinging, sea spray.

Fortunately the ship was such a large and well constructed craft, that the storms efforts did the vessel little harm. The approach of the stormiest weather was always indicated by the ship's barometer and the officers and crew were thus prepared for the onslaught, but most of the passengers were not, and many, once again, suffered the effects of sea sickness. With Captain Forbes in command the sails were often filled under a strong breeze, and on many occasions the ship forged ahead at the rate of 18 knots an hour, and in one 24 hour period off the Cape it was calculated that we had travelled 350 miles. On these record breaking days I recalled the Captain’s statement at the start of our voyage, when he told us he had no intention of bad weather or storms delaying his arrival in Melbourne in record time. It seems he has not changed his mind.

We are, it seems, off the southern coast of our new homeland, and although we cannot sight it as yet, an unusual smell seems to be blowing across the ship from the coast. It’s not particularly pleasant and I’m told it’s the scent of the land. Sea birds are now following the ship and many of the male passengers are eager for some sport and to try out their pistols and firearms in an effort to shoot them down. One passenger reported to the captain that he had overheard a group of men who were plotting to shoot another passenger by the name of Albert Ross. The captain was at first concerned with this allegation until it became clear that the men were in fact trying to shoot a giant seagull called an albatross. We will shortly be changing direction and heading north towards the Bass Straight and on towards Port Phillips Head and Melbourne, and this sport of sea bird shooting will have to cease as we approach, much to the relief, I'm sure, of anyone on board who is unfortunate enough to actually be called Albert Ross.

This is now the 1st of Sept. and a great excitement is evident throughout the ship as we have finally came insight of the coastline of our final destination, we sailed very close to Cape Otway on the southern tip of Australia, and a great cheer from all aboard arose as we passed by. The smell of the land is stronger now and I must admit that as it's strength increases it's not the most agreeable aroma to grace my nostrils. The weather is much calmer now of course, and the normal strong winds that have driven our ship here, have given way to a warm and comfortable fresh breeze, that is very pleasant.

16th of September and we have dropped anchor in the East Channel inside the Port Phillip Heads, while we await a pilot to guide us into our final berth. The Captain has decreed that our passage time is counted from the 4th of July to this point, thus making the passage from land to land in a total of 75 days.

On the 18th we took aboard our pilot, a gentleman by the name of Mr. Steel. The captain was keen to advance, and once the pilot was aboard he quickly set sail and entered the bay. On going in we saw the wrecks of two ships who's captains had thought it unnecessary to obtain expert advice. As we thought that our captain had been much wiser in retaining the services of an experienced pilot, the ship gave a mighty groan and quickly ground to a halt. Much to the annoyance of the captain, we found we had struck a sand bank and our ship was in a precarious position for a time. The captain and the pilot were soon arguing about their predicament with each one blaming the other. Nonetheless we were stuck and remained so until high tide on the 19th when we eventually got off. We then continued on into the bay, and at 11 am on Monday the 20th of September 1852, we dropped anchor at Port Phillip Heads.

Monday 20th September 1852. So, 78 days out of Liverpool and at last I find myself, if not actually on Australian soil at least in sight of this great land. The journey is finally over, and I feel as though I have been delivered from the gates of hell itself. We have arrived ahead of the new steamer “Australia”, although we don’t expect it to be far behind us, * It was in fact another week before the steamer arrived. The mate has told me that the voyage has been completed in record time, and that we have made the quickest passage ever achieved from Britain to Australia. But the eleven weeks I have endured aboard this ship have been in the most part uncomfortable and disagreeable and I thank God that it’s almost over.

This journey from the dear green hills of New Cumnock to the vastness of Australia has been an experience, and I have learned a great deal from it. I am greatly saddened however about the loss of so many young lives, the Australians, who never quite arrived. I’m told today by Dr. North that 52 children died on the voyage along with 2 adults. In the doctors opinion most of these deaths were due to the epidemic of measles that took hold after only a few days into the voyage, and the two female adults were sickly upon our departure from Liverpool. Although these deaths have caused great sadness and unbearable grief to the affected families we must give thanks to God that we had no fever of any kind during the voyage. This has ensured that many more people survived this terrible voyage. As I look out over the bay I can reflect upon this voyage and remember the times, when the winds were favourable, and the ship forged ahead, but then I recall other occasions when we were becalmed for days due to a lack of wind. For the crew and passengers alike, regardless of their time spent at sea, there were many moments of peace and solace, however I also experienced great fear, and many moments of terror also abounded.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.