by Elaine Corbett

The discovery of rich mineral deposits in West Cumberland became an ideal point of convergence for a huge number of workers in the 19th century.

Francis Carter was born in 1857 in Lamplugh, Cumbria, the first son of Irish immigrants William Carter and Elizabeth Doyle. They had been married in Whitehaven in 1856. The 1861 census tells us that Elizabeth had come from Wexford, along with her brother Patrick and their mother. Along with William Carter they had come to West Cumberland attracted by the prospect of employment and had eventually settled in the small hamlet of Skelsceugh in the centre of a group of iron mines around Winder, Frizington, and Rowrah.

William Carter became an iron miner. The Doyles, also iron miners, lived a few doors away at Skelsceugh, and both the Doyles and the Carters had their first children in Lamplugh.

At the age of 13 Francis was listed as an iron miner in the census.

Francis would have been born in a typical two up, two down miners’ terrace house surrounded by open fields, and spoil heaps from the mines. There would have been worksheds and winding gear built around the mine shafts, and the landscape was criss crossed with train tracks trundling the tubs of ore.

Just to the north of the Winder mines, the Kelton and Knockmurton mines in Lamplugh were large producers of iron ore. The mines were owned by William Baird & Co of Gartsherrie, Scotland, who had ventured south in search of quality ore for their blast furnaces. Between 1869 and 1913 over 1.25 million tons were raised, much of which was transported to their works though some went to the Moss Bay and Harrington furnaces on the west coast, and a little to the Midlands.

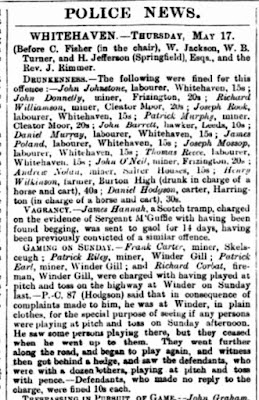

This is the little engine built by Neilson and Co. to draw the ore wagons and bought in 1876 by William Baird and would be a familiar sight to Francis. The Kelton Fell now on display at the museum of Scottish Railways, Bo’ness and Kinneil Railway museum. Photos from Elaine Corbett.

In the census, Francis gave his birthplace as Lamplugh, while the rest of his siblings seem to have been born in Skelsceugh, so perhaps William, his wife Elizabeth, and the rest of her family, the Doyles came over to work in the Lamplugh mines of William Baird and Co.

Winder Mines link to maps

|

| Holbeck mine owned by Dalmellington, Frizington |

Another link to the Cumnock mining area can be seen in the name of the mine shown in the map above. This one would also be within walking distance of the Carter and Doyle families, although it was common for miners to hitch a ride on the ore wagons to get to their place of work.

The Dalmellington Iron Company, opened the Holbeck Mine in 1869 and worked it until its closure in 1900. Holbeck mine was a wet mine. In addition to the discomfort of working underground, the miners were persistently wetted with water dropping from the roof, and seeping through at the sides of their excavations. They came home wet every night, and cold in the winter. The stream running above the mine workings was encased in concrete and walls built to prevent overflow, and although the ammount of water was much reduced, the conditions were still poor.

At the age of 24 Francis, his parents, his six siblings, and an Irish boarder are all living in the same house. How did they all fit in I hear you ask? But most properties housed a boarder in addition their often large family. The usual haunt of the working man was the nearest public house where they could slake their thirst, escape the children, smoke their pipes and play dominoes.

Francis had joined his father among the ‘red men’ as yet another iron miner. Children often followed their fathers into the mine work, starting young and being mentored by their parent or uncle. Typically, iron mines would employ around 50 men and boys in small teams with a team leader. This mode of working helped foster a team mentality wherby each of the team members would look out for one another in terms of safety. If an accident happened to any of the team members - and accidents were worryingly frequent - there were many acts of valour among the team in recovering the situation. The Durham Mining Museum website lists all the mines in West Cumberland and details the fatal accidents and inquests held at the hotel a stone’s throw away from Francis’ house. A common theme would be deaths caused through falls from height, crushing injuries from contact with ore wagons, and roof/side rock falls. At the Inquest it is remarkable that most record no fault on the part of the mining company.

The ore was blasted into rubble in the Room and Pillar method of working, the roof would be shored up and the ore shovelled into tubs. Miners were paid by their team leader based on the quantity of ore they extracted.

The working conditions in the mines were poor. There were no facilities at the mine for showers or sanitation. The lavatories were basic, two old tar barrels were reported as the norm. It wasn’t until 1950 that showers were provided.The men and boys came home coated in the red dust of the ore, and would have breathed in considerable ammounts of it, along with the fume from explosives, during their often short working lives. Their clothes would be dried overnight at the fire to be worn again the following day. There was no escape from the red dust, or mud in the case of wet mines. The bedclothes were stained with it, streams ran red with it, and the hemlines and petticoats of the wives and daughters were stained with it.

There was a general belief held among the medical profession as well as the miners, that the iron dust was more harmful to the lung than coal and this may have been a consideration that persuaded Francis to leave for the coal fields of Cumnock. Another consideration of course is the pitiful wages that iron miners commanded, with most of the profits seemingly going to mine owners and land owners.

The population of West Cumberland was swelled by the arrival of Irish workers. Around this time, mine worker terraces, Catholic churches and schools were built to accommodate them. This was the time of a great boom in iron extraction, and gave the area the nick-name ‘The Klondike’.

There was however, a sectarian divide arising from the influx of mainly Roman Catholic Irish workers with matters reaching a low point in the so called Murphy riots. The notorious anti-Catholic William Murphy was attacked by 300 Cleator Moor iron-ore miners at Whitehaven in 1871. At the time of the Irish Potato Famine, mining and associated jobs were plentiful and all of the West Cumbrian towns such as Whitehaven and Workington as well as large villages like Frizington and Cleator Moor developed sizeable Irish populations with the mix of Catholics and Protestants providing potential for sectarian quarrels. Murphy, a notorious anti-Catholic came to Whitehaven in April 1871 the Magistrates decided to allow him to speak in the Oddfellows Hall only for him to be attacked by 300 well-drilled iron-ore miners from Cleator Moor and around. The police, caught unawares and hopelessly outnumbered, could do little for him and before a rescue could be effected Murphy was horribly beaten. It was some weeks before he recovered sufficiently to face his attackers in court. As consequence five men were given 12 months with hard labour and two got three months. Murphy came back to the town in December, despite the entreaties of the local magistrates, but events passed off relatively smoothly. In March 1872 he died, Birmingham surgeons claimed, because of the lingering effects of the savage assault dished out by those Cleator Moor miners. The Press was horrified that a man could die for his views and there followed an Orange revival in Cumbria. Until recently Orange parades were a regular feature in West Cumberland.

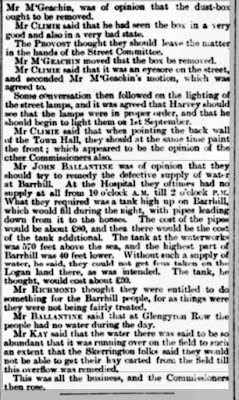

There was only one newspaper clipping from this time that I found, which suggests that Francis was not particularly devout, and no indication whether he was Catholic, Protestant or of any religion at all.

From the Cumberland Paquet 1877…

The other people mentioned in the article are also miners, or have jobs associated with the industry, and gives an idea of what life was like in the ‘wild west’ at this time. Pitch and Toss seems rather tame in comparison.

The Legacy.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.